How It’s Done Here: North Bay Rapid Response Network, California

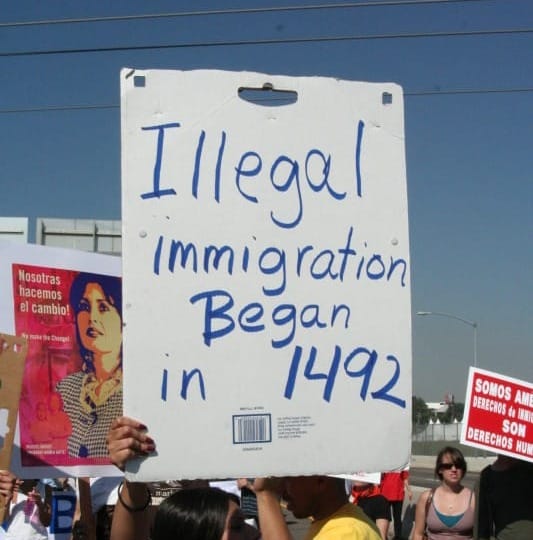

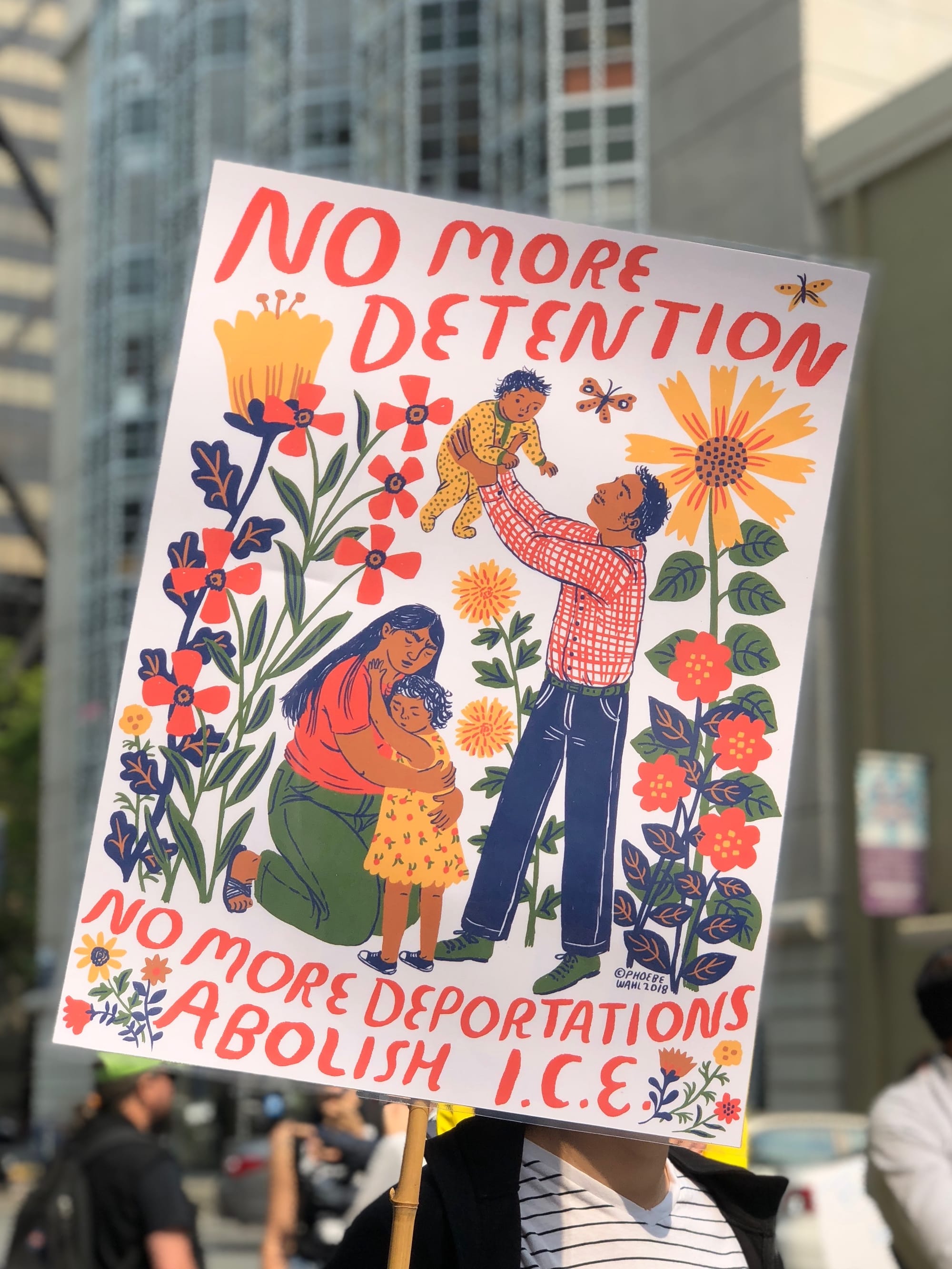

Trump 2.0’s plan to remove undocumented immigrants from the U.S. through mass deportation is leading immigrant solidarity networks to widen their reach and mobilize community action. Under the plan, Trump says he will deploy the U.S. military, along with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—who will partner with local law enforcement agencies around the country to detain and deport our community members under the guidelines of the 287(g) program—to ensure the mass deportation project is successful. Yet, instead of spreading panic, many mutual aid groups are acting now to support immigrants. From lifesaving efforts in the vast swaths of rural border regions, to legal clinics supporting folks through often complicated paperwork, momentum to protect our most vulnerable community members is growing.

One such project in Northern California offers support in the form of legal observations during ICE activity, education and outreach for immigrants and their employers, and accompaniment during immigrant court proceedings. The North Bay Rapid Response Network (RRN), a project of North Bay Organizing Project, a grassroots, multiracial, and multi-issue organization that “unites people to build leadership and grassroots power for social, economic, racial and environmental justice,” has done all of this and more since its founding in 2017. The network operates a hotline that connects callers with advice, legal observation teams, and support when facing deportation.

North Bay Rapid Response Network operates like the national MigraWatch program which manages a hotline to report ICE and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) raids and other activity. The approach to observing ICE through these networks is similar to CopWatch, which was first founded in Berkeley, California in 1990 in order to hold police accountable for violence and other misconduct through observing and documenting their activity.

“During the election of 2016, knowing that there was an administration coming in who was going to be, what would I say, rabidly harsh with immigration issues, a great many members of the community looked around and thought, ‘We need to make sure that mass raids and deportations don’t happen here,’” says RRN dispatch coordinator, Vikki DuRee.

During those days leading up to the 2017 inauguration, DuRee says she and others started off as a pilot group that came together with representatives from various nonprofit, organizer, and church-affiliated organizations. Their goal was to create a network to support immigrants who might be targeted, and the result was establishing the RRN hotline covering the tri-county region of Napa, Solano and Sonoma Counties, just north of San Francisco.

The region is home to roughly 65,000 undocumented immigrants, working largely in the area’s abundant agriculture industry; the bulk of these workers pick grapes in the widely idealized and affluent grape-growing and wine making businesses that have pushed out most of the traditional apple and other fruit orchards that used to blanket much of the region, particularly in Sonoma County. The wine industry in Sonoma County is the county’s largest employer, worth more than $1 billion. Many other undocumented folks here also make up much of the workforce in the hospitality and tourist sectors, another huge aspect of the local economy.

The Rapid Response Network is impressively organized, with over 700 trained legal observer volunteers, around twenty-five trained dispatchers and another 20-50 accompaniment volunteers, which provide support on the community level; driving people to their ICE appointments, to court appearances, helping asylum families enroll children in school, to get medical coverage, to plug into basic community services. The various volunteers are peppered throughout the 3,200 square miles of the service area. The network is parceled out into regions, with the bulk of volunteers in Sonoma County. Around 5-10 legal observers are sent to sites of ICE activity, with each person taking on specific roles: recording, photographing, notetaking, acting as a community liaison, and so forth.

Another mutual aid effort of the network is outreach and education. The hotline phone number is printed on cards and distributed widely.

“If someone calls our phone number, we have dispatchers fielding those calls. And if there's an ICE presence or a suspected ICE presence, for example, then we activate our observer network and the legal observers who have been trained by our teams go out into the community; we're able to send them to the site of the suspected sighting,” says DuRee. “And then they have steps they take to either confirm what kind of presence is there. They are also trained to document so that in the event of a real ICE action, there's some documentation that the affected community members can use in their removal defense.”

Some information dispatchers share with callers is that ICE must have a warrant signed by a federal judge in order to detain undocumented folks, and that ICE cannot enter an area marked as private property. Keeping gates closed with clear signage like NO TRESSPASSING/PRIVATE PROPERTY should deter federal agents from entering property. However, we know that law enforcement agencies of all kinds rarely play by the rules, hence the importance of legal observers documenting their actions to help build a strong case on behalf of the targeted and detained.

DuRee says that while RRN does make legal referrals, the network’s legal partners are “absolutely swamped” and there is an overwhelming demand for attorneys specializing in immigration law. In the case of a detention, she says, RRN has partners in San Francisco through California Collaborative for Immigrant Justice (CCIJ), an organization with the mission of utilizing “coordination, advocacy, and legal services to fight for the liberation of immigrants in detention in California.”

If someone—or a group of people—is detained, dispatchers contact CCIJ immediately, to alert them that people have been detained and are in ICE custody.

“In our early years, we were able to get lawyers in San Francisco in time to, at times, intervene and at least provide support and information to the affected person. In recent years, ICE is very quick in their transfers, and it's much harder to get people to San Francisco to the processing center,” says DuRee. “We find that for a morning detention in Sonoma County, by the end of the day, they're already in a detention facility down in Bakersfield or San Diego. It's very quick now, and we imagine that they sped up the process precisely because of the community mobilization.”

Bystanders have stepped up to document things like police brutality, obnoxious Karens attempting to shut down BBQs and kids’ lemonade stands in recent years, but for folks not trained to observe and document ICE activity, specifically, DuRee says it can be a tricky situation to navigate.

“We don't want people walking into a potentially volatile situation, and we certainly don't want to make things worse for the people who are the target,” says DuRee. “It could be DEA, it could be sheriffs, it could be Homeland Investigations.”

Still, community members may be inclined to do something helpful when they witness ICE cracking down on their family, friends, and neighbors. The main suggestion DuRee has is to call the hotline so dispatchers can deploy trained observers. Next, to avoid confrontation or escalation, bystanders should not obstruct the activity, and should remain on the sidelines, taking photographs, observing and noting, and call in to dispatchers to share what those observations are; that helps folks on the other end of the hotline know where to send people, how many people to send, and what kind of action might be unfolding.

Another likely scenario that folks might see is ICE agents gathering in a parking lot before heading to conduct a raid. If someone observes a cluster of vehicles or a vehicle that they thought was an ICE vehicle, for example, they can take a photo of it and report it to the hotline for dispatchers to verify before sending observers.

For employers who have undocumented folks on staff, there are some tips for workplace protection and workplace advocacy that ensure legal limitations to ICE if they are exercised. Employers should mark their private areas as: PRIVATE. EMPLOYEES ONLY. NO ENTRY. Keeping gates to properties closed and posting: PRIVATE PROPERTY, DO NOT ENTER is another measure employers can take that provide legal protection for their workers.

For folks who want to support these networks but can’t engage directly because of accessibility, legal, or other issues, DuRee says there are several ways to help.

“Those groups generally need resources; money for gas, money for bridge tolls, money to buy grocery cards or gas cards for the families that are being supported,” she says. “And let your affected community members know that you're with them.”

No administration will save us and our undocumented siblings. We all need to step up to save ourselves and each other. According to the Migration Policy Institute, 1.1 million deportations occurred during Biden’s presidency between the beginning of fiscal year (FY) 2021 through February 2024. “The Biden administration’s nearly 4.4 million repatriations are already more than any single presidential term since the George W. Bush administration,” they stated in a June 2024 report. Because a significant number of the deportations under his administration took place at border crossings, they went largely unnoticed. Now, as Trump prepares to take office again—and his rhetoric is more aggressive and violent toward our immigrant community—people are paying more attention and preparing to act.

Moving forward into 2025, the Rapid Response Network is ramping up their community engagement efforts. They’ve recently restarted their trainings for legal observers and hotline dispatchers, and trainings to grow their network of folks who can go out and train even more observers. They are receiving phone calls from school districts and employers on how to keep students, families and employees safe from ICE, so network volunteers have been providing them with information and materials, including the hotline cards. Other mutual aid networks have started hosting Know Your Rights trainings and events and RRN has spread information through them, as well.

The ramifications for the country if Trump’s plans succeed will have sweeping detrimental impacts on all of our communities; the economic impact will be tremendous, yes, but let’s maybe reframe the idea of immigrants as simply cogs in the machine keeping America running, and think of immigrants instead—first and foremost—as human beings. The Rapid Response Network will continue working toward a community of care for everyone, reminding us that it is indeed us—the community—that keeps us all safe.

To get involved with national MigraWatch, visit United We Dream

For more information and resources to support our immigrant neighbors visit: